Learn how to make

your own lye from ashes, and then

use it to cook up a mild, soft soap perfect

for personal use.

By Susan Verberg

Soap-makers love to tell the story of how ancient Romans first

“discovered” soap by burning animal sacrifices on Mount Sapo,

and how the creeks at the bottom of that mythological mountain were the best

places to do laundry. They’ll tell you that the water, ash and animal fat on

those sites accidentally created the soap that filled the creeks. The reality

is that the Romans didn’t actually make soap. They traded for it with the

Celts, who dominated the market because of their access to abundant limestone

and seashells [writer's note: this would be access to marine plants for

soda ash as opposed to potash, not limestone which is calcium oxide], from which they produced slaked lime [soda ash] to make a caustic soda lye

(sodium hydroxide).

After years of professionally making all-natural goat’s milk

soaps to sell at our local farmers market, I decided to develop a

self-sufficient soap-making process based on ancient techniques. My goals were

to make my own lye and to turn kitchen-waste fats into soap. I finally took the

plunge… and what an interesting adventure it became! I dug through old articles

and manuscripts, learned to decipher medieval English, and filled my kitchen

with weird, bubbling concoctions. And I wondered how something that seemed so

simple could be so challenging.

Don’t let me discourage you. If you’re an outdoor

enthusiast, you may have made soap already. Scrubbing a greasy frying pan with

campfire ashes doesn’t just scour the dirt away: when rinsed with a little

water, the hydroxide salts in the ashes combine with the cooking grease to form

a primitive cleanser.

Understanding Soap-Making Basic

To undertake the process of soap making, known as “saponification” (from sapo, the Latin word for

soap), let’s first review what soap is and why it works the way it does.

Because soap is made from water-soluble bases known as alkalis, it neutralizes

acids while retaining its ability to be dissolved in water. More specifically,

soap is a surfactant with the unusual ability to diffuse fats and oils into

water, which is why it can rinse away oily stains.

Soap is made by mixing dissolved hydroxide salts, generally

called “lye”, with fatty acids. To make your own lye that you can use to

produce a soft soap, you leach (or drip) water through ashes to dissolve the

hydroxide salts. Ashes are highly concentrated minerals of hydroxides,

nitrates, carbonates, sulfites, and more. The quality of the lye produced

depends on how well the plant material was burned. I’ve found that the more

complete the burn (all organic material combusted), the more hydroxides will be

dissolved, and the more basic (that is, higher pH) the resulting lye will be.

In the case of incomplete burns, such as you’d find in fire pits and fireplaces,

you can add lime to help change the carbonates (charcoal) into hydroxides.

My drip lye made from ashes has a pH of about 11, while commercial

lye has a pH of 14 – making it 1,000 times more basic than ash lye. This is a

big reason why making drip-lye soap is so different

from conventional soap making. Because of the lower pH, drip lye is a

lot less dangerous to handle than modern commercial lye. As a precaution,

though, you should always keep some vinegar handy during soap making because

its acid will help neutralize the lye’s base.

Making soap using drip lye can be challenging because the

purity, density, and consistency of home made lye is uneven. For home

soapmakers, I recommend preparing hot-process soap (which I describe below)

rather than cold-process because an exact amount or specific purity of lye isn’t

required for successful saponification. In hot-process soaps, saponification –

the chemical reaction between lye and fat – is controlled by added heat, not by

the pH.

During my research, I uncovered a historic trick for

checking the density of drip-ash lye using a fresh egg. Because an egg has

about the same density as lye that’s the correct strength, the egg will float.

Many colonial recipes for drip-ash lye recommend using homemade lye if it can

float an egg with ¼ of its shell showing about the liquid. This lye will

produce “Black Soap”, a strong laundry soap that historical re-enactors

complain is too harsh. On the other hand, I uncovered a 16th century

shampoo recipe that recommends using lye dense enough to suspend an egg in the

middle of the liquid. Suspended-egg lye makes near-neutral soap, perfect for

personal use because it does not “bite”. This same historic recipe also

confirms the 3-to-1 ratio of lye to fat that consistently works for me: “thre

pottels of lye to one pot of oyl”. It’s nice to find confirmation that’s five

centuries old!

Based on experience and historical research, I’ve developed

these instructions for making a soft, creamy, hot-process soap from scratch –

including homemade lye.

Soft Soap in 8 Steps

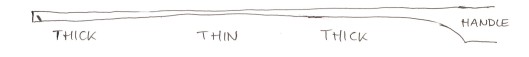

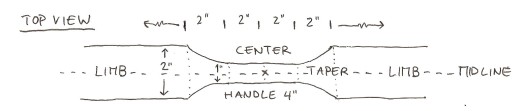

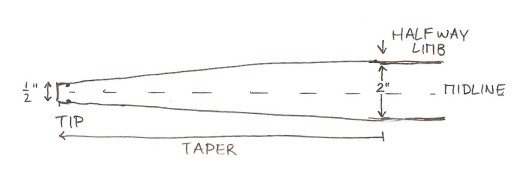

1 - To make a leaching barrel, drill a small hole at the

bottom of a 5-gallon bucket and stuff it with a piece of dishcloth as a filter.

Fill the bucket with sieved ashes, tamping down intermittently. Level the top,

leaving about 2 inches of headroom. Slowly pour in about an inch of rainwater.

When the water has absorbed, add about an inch more. Continue to slowly add

water until liquid starts to drip out the hole in the bottom of the bucket – it

should take about a day. Prop the ash bucket on top of a second bucket to

collect this drip lye. (Or build a setup like in the illustration at the left.)

You’re ready to test the strength when you’ve collected about 1 gallon.

2 – If you’ve used regular ashes from a woodstove or

fireplace in Step 1, the drip lye will be dark brown and probably won’t suspend

an egg. Slowly heat the the drip lye and allow it to evaporate until it has the

desired strength, which is likely to about a quarter of its original volume.

Use stainless steel vessels for heating lye, never aluminum (which creates

noxious gases in combination with lye) or enamel (which lye will etch). Cool

down the lye before soap making. Contaminants will settle to the bottom. The

next day, pour the purer lye solution off the top (that is, decant it). If you’ve

used white ashes from a high-efficiency stove in Step 1, the lye may be light

yellow and will float an egg from the get-go. Use this lye as is to make a

strong, sharp laundry soap. To make neutral hand soap, slowly add water in

small amounts until the egg is suspended in the solution.

3 – Measure out (by liquid volume) 3 parts lye to 1 part

oil. Fats that are solid at room temperature, such as tallow and lard, should

be heated until they liquefy, and then cooled. If you’re a soap-maker beginner,

use olive oil because the process will be easier. Add the lye to the oil and

mix well – a stick blender works great – and let sit overnight.

4 – After 12 hours rest, the solution will have separated.

Mix it very well. Heat the solution for an hour or two in a slow cooker on the high

setting with the lid in place. Stir only occasionally, as the soap should not

be allowed to cool down. When the soap starts to rise, you’ll see foam forming

under the lid. Remove the lid, and stir the soap well to settle the foam.

Replace the lid, but prop a toothpick under the lid to create a little gap for

hot air to escape.

5 – As the soap cooks in the slow cooker (still on the high

setting), you’ll see bubbles form at the edge of the ceramic insert. This is

the soap “turning itself”. It should only bubble at the edges – never boil in

the center. You’ll observe finished soap starting to form on top. Stir

occasionally to ensure that no areas dry out at the edges of the insert. Be

sure to stir gently, because the mixture can foam up suddenly at this stage.

6 – The soap will get thicker and thicker until it

incorporates, or finishes. Remove the slow cooker’s lid so excess moisture can

evaporate. This soap will look like custard (soap-makers call this “trace”),

leave droplet marks (“trace marks”) on the surface when scooped and drip off

the spoon in globs. You’re nearly finished!

7 – Cook until it starts to have a glazed, sleek look, like

petroleum jelly, and leaves little wavy points when stirred. If you part the soap

at the bottom of the cooker, it should not come back together. Stop cooking at

this point for a thin, soft soap. Or, keep evaporating the moisture until the

soap is your desired density – it will never get hard. I prefer a whipped cream

consistency.

8 – Your finished product will vary by color and

consistency. I’ve made successful batches of soap using “old-fashioned” techniques

and each one takes about six to seven hours. If you decide to try this process

over open heat, be aware that a more erratic heat sources will make the soap

behave erratically as well, and your mixture may not come to trace.

Making soap from homemade drip lye is a fun and rewarding

project, and one that doesn’t require specialized or expensive equipment. I

hope you’ll give it a try!

From the December 2016/January 2017 Mother Earth News issue, page 40-42.